Japan, mon amour

Land of my dream

The Japan of my Dream is not a geographical location but a specific mindset, a pattern of subtle attitudes and abstract concepts that express a certain aesthetic, an atmosphere that is very attractive to me….

Dont ask me why, since i have never set foot on this land …

Yet, i love it when i see it …

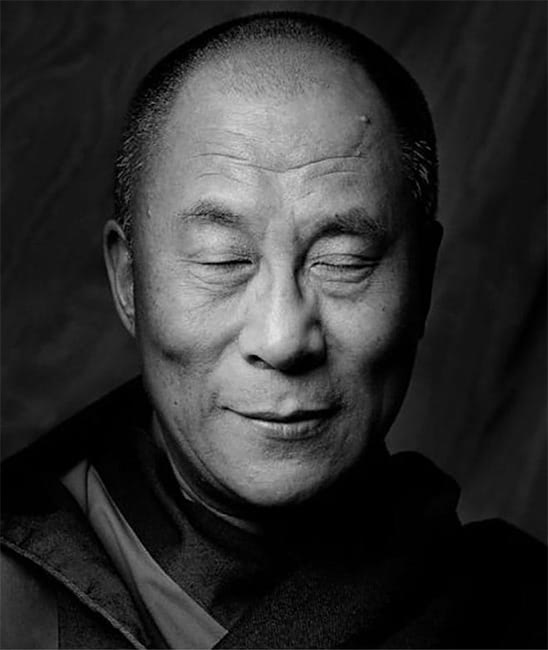

Maybe this spontanious love is grounded in my affinity to the Buddha’s early teachings, which have a strong echo in

Japanese Zen Buddhism …

Maybe it is my affinity to minimalism and intentional simplicity in life and art …

Maybe i just like the use of whitespace / negative space in graphic design …

Maybe i actually dont need to know why i love Japanese aesthetic concepts and the deeper philosophical and spiritual principles that govern(ed) traditional Japanese society and shape(d) minds and attitudes of the Japanese people.

Maybe i am simply sensing the Soul of Japan …

I take refuge in the concept of “uryū monji” / beyond words, which is the Zen teaching that truth cannot be grasped through language alone. The deepest insights are lived, not spoken.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

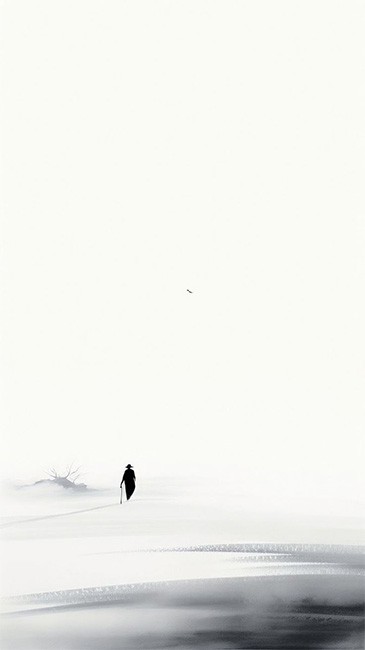

花鳥風月 – Kachōfūgetsu

The beauty of nature

“Flower, bird, wind, moon.” This classical phrase evokes the sensory beauty of the natural world. To appreciate kachōfūgetsu is to be fully alive to the seasons, the weather, the small wonders of each day. It is poetry without words.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

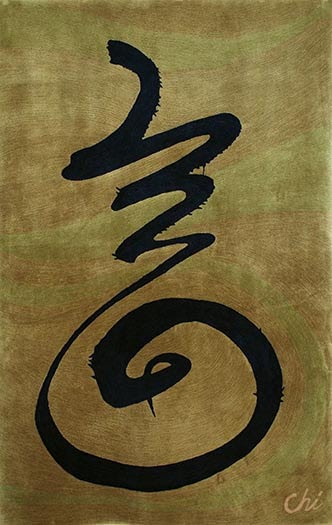

気 – Ki

The flow of life energy

“Ki” is the invisible energy that animates all things. Similar to “chi” in Chinese philosophy, it flows through breath, movement, and emotion. Ki is in a gesture, a glance, a silence. When it is blocked, we feel dis-ease. When it flows, we feel alive.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

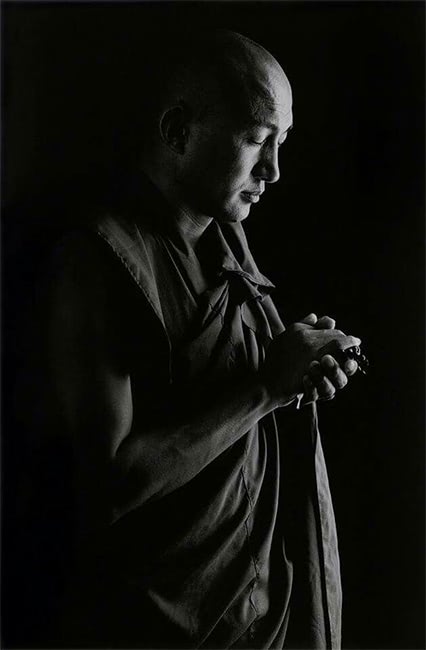

空 – Kū

The emptiness that holds all things

“Kū” is often translated as “emptiness” or “void,” but it is not nothingness. It refers to the Buddhist concept of form being empty of fixed nature—impermanent, interdependent, and constantly changing. In life, Kū is the spaciousness that allows transformation. It is the silent potential in all things, the breath before form arises.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

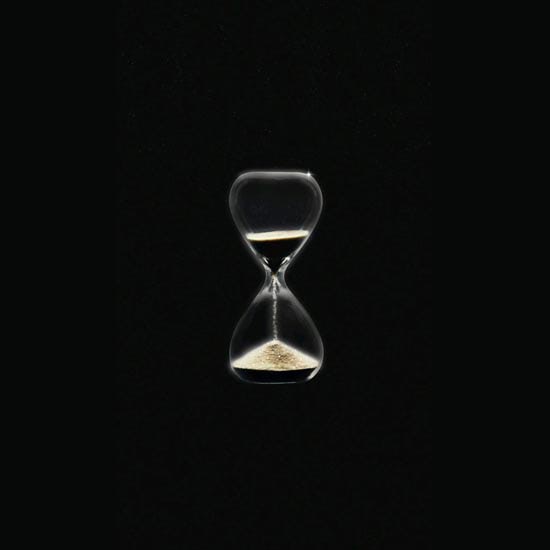

無常 – Mujō

The truth of impermanence

“Mujō” is the Buddhist teaching that all things are transient. Life, youth, success, suffering—all pass. Far from nihilism, mujō invites appreciation. Because everything ends, everything matters. A falling leaf is not a loss—it is a lesson.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

無 – Mu

The absence that reveals truth

“Mu” means “not” or “non-.” It is a core Zen principle, often used to negate dualistic thinking. In a spiritual sense, Mu is the letting go of fixed concepts, of having or not having. It is a gateway to understanding beyond logic. To dwell in Mu is to meet reality without expectation or attachment.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

不立文字 – Furyū monji

Beyond words

“Furyū monji” means “no reliance on words or letters.” It is a Zen teaching that truth cannot be grasped through language alone. The deepest insights are lived, not spoken. The finger pointing to the moon is not the moon.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

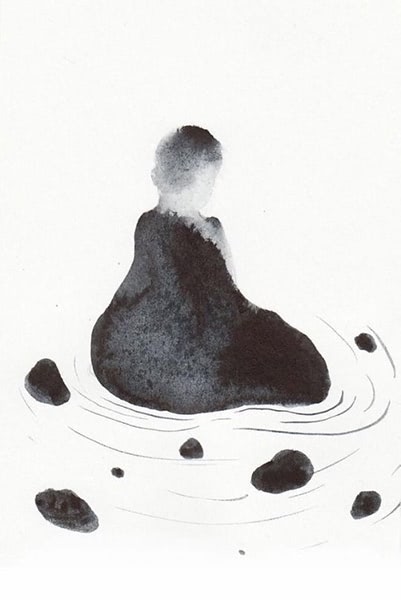

静寂 – Seijaku

Sacred stillness

“Seijaku” means deep quietness. It is not mere silence, but a stillness that contains peace, depth, and clarity. Found in Zen gardens and in the pause before action, seijaku is the well from which inner calm can be drawn, even in the midst of chaos.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

余白 – Yohaku

The art of blank space

“Yohaku” refers to the blank margin—the space left intentionally unfilled. In painting, it invites the viewer’s imagination. In life, it creates room to breathe. Yohaku is not a void but a quiet openness that honors what is not said, not done, not crowded.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

間 – Ma

The space between things

“Ma” is the interval—the space between two notes, two words, two movements. It is not emptiness, but a presence made of absence. In aesthetics and daily life, Ma allows rhythm, grace, and meaning. A well-placed pause is often more powerful than speech.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

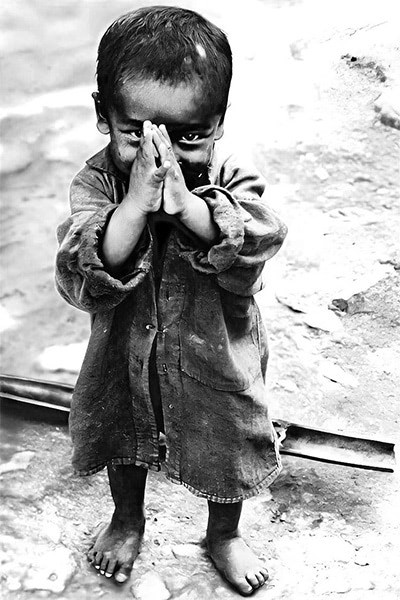

侘寂 – Wabi-Sabi

Admiring imperfection

The Japanese aesthetic of “wabi-sabi” means finding beauty in what is impermanent and imperfect. In other words, it is the Zen Buddhist concept of beauty seen through appreciating the imperfections in nature in which everything is impermanent. The philosophy nurtures all that is authentic by acknowledging three basic truths: nothing lasts, nothing is finished and nothing is perfect. In a personal sense, it means graciously accepting my own and others’ flaws.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

蒔絵 – Maki-e

Scars turned into gold

“Maki-e” is the ancient art of sprinkling gold or silver powder onto lacquerware. Cracks and broken surfaces are not hidden but highlighted. It is kin to the idea of kintsugi—beautifying flaws rather than erasing them. Maki-e is a way of living: to honor what has been broken and to restore it with grace.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

生き甲斐 – Ikigai

The reason for being

“Ikigai” is a person’s sense of purpose, the thing that gives meaning to waking up each day. It arises at the intersection of what you love, what you’re good at, what the world needs, and what you can offer. It need not be grand. Even a quiet joy can be ikigai.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

我慢 – Gaman

Dignified endurance

“Gaman” means patience and perseverance, especially in the face of hardship. It is enduring with dignity, self-control, and quiet strength. Rooted in collectivist culture, gaman is often practiced without complaint, as a way of honoring others and oneself.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

恩 – On

The burden of gratitude

“On” refers to the deep, often unspoken obligation one feels after receiving kindness or care. It is not transactional, but sacred. On can last a lifetime. Repaying it is not a duty—it is a moral compass rooted in respect and relationship.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

気配 – Kehai

The presence felt

“Kehai” is the subtle sense of someone or something being there—before it is seen or heard. It’s the intuition of a presence. A shift in the air. Kehai teaches sensitivity, awareness, and respect for what is unspoken.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

不動心 – Fudōshin

The unmoved heart

“Fudōshin” is the ideal of a warrior’s mind—calm, unshaken, centered. It is not passive, but poised. Fudōshin means responding without anger, deciding without haste, standing firm in purpose. Like a pine tree in winter.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

大和撫子 – Yamato Nadeshiko

The quiet feminine ideal

“Yamato Nadeshiko” refers to the traditional image of Japanese womanhood—graceful, modest, resilient. She does not seek attention, but commands respect. She is not weak, on the contrary; her strength is quiet, enduring, and deeply rooted.

In the movie “Shogun” those qualities are personified by Toda Mariko, a highly intelligent women of profound depth, mystery and fierce loyalty.

She is elegant and beautiful, poised and dignified. Outwardly she is kind and gentle but with unmistakable inner strength and quiet determination. She has a nurturing yet uncompromising and firmly loyal personality.

Although the book and the movie are Historical Fiction, her character – based on the real life of Hosokawa Gracia (1563-1600) – channels many of the qualities of Old Japan that i tried to describe in this article.

Although the movie did not really make me loose my sleep, it goes without saying that i could not help but fall in love with this “dream lady” 😃 and her – very yamato nadeshiko – qualities …

Yamato nadeshiko – flower of the Japanese nation

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

It is obvious that here i am not talking about the modern Japan, which i see as a rather puzzling and contradicting mix of hyper modern and traditional views, smells and sounds.

I guess i am trying to convey what i understand is the soul of Japan, attitudes and qualities that are still present in the countryside, in people and i think will live on. Cause the soul of a nation never dies.

I believe there is a need of our rather loud and superficial western over-civilized culture to consider such values and attitudes of subtlety, as present in the “olden days” of Japan.

You are welcomed to read my article: “An exploration into nuance and subtlety. And the art of cultivating The Subtle in everyday life.”

.

. .

. . .

. .

.

.

. .

. . .

. .

.